I’ve been playing the trombone since fourth grade. Today, I’m going to share what I’ve learned about, especially the technical aspects of playing such an instrument.

But first, what’s a trombone?

To understand why playing the trombone is so different, let’s first look at the instrument itself.

Pictured here is a Yamaha tenor trombone. It’s very simple to assemble as it’s just 2 parts: the horn and the large tuning slide.

The trombone is the only brass instrument in a classical orchestra (I specify classical because variations such as the superbone also exist) where the main mode of pitch control is by moving the tuning slide. This means that, like string instruments (violin, viola, cello, etc), the pitch is continuous: I will get into why this is important later. But for now, one obvious advantage is that this allows us to do “real” glissandos, where the pitch smoothly transitions from one note to another.

As a brass instrument, you also “buzz” into the metal mouthpiece in order to play the trombone. “Buzzing” is the act of vibrating the lips against the mouthpiece to produce sound. If you just relax your lips and blow air (without vocalizing any pitch), that’s pretty close to what we call a “buzz”.

On a piano, you just press a key to play a note. For a trombone, you change the “slide position” where extending it makes a lower note.

Of course, since there’s only 7 slide positions (where 1st position is where the slide is fully retracted and the 7th is where the slide is fully extended), you would also need to adjust your embouchure (the way you shape your lips and tongue) to get to different “partials” to hit higher or lower notes.

To understand how that works (one of the hardest parts of playing a brass instrument), we need to look at the standing waves inside the trombone.

Side note: while the mechanics of this is technically the same for all wind instruments, the trombone is also unique in that it’s the most visually simple example of this system.

Physics!

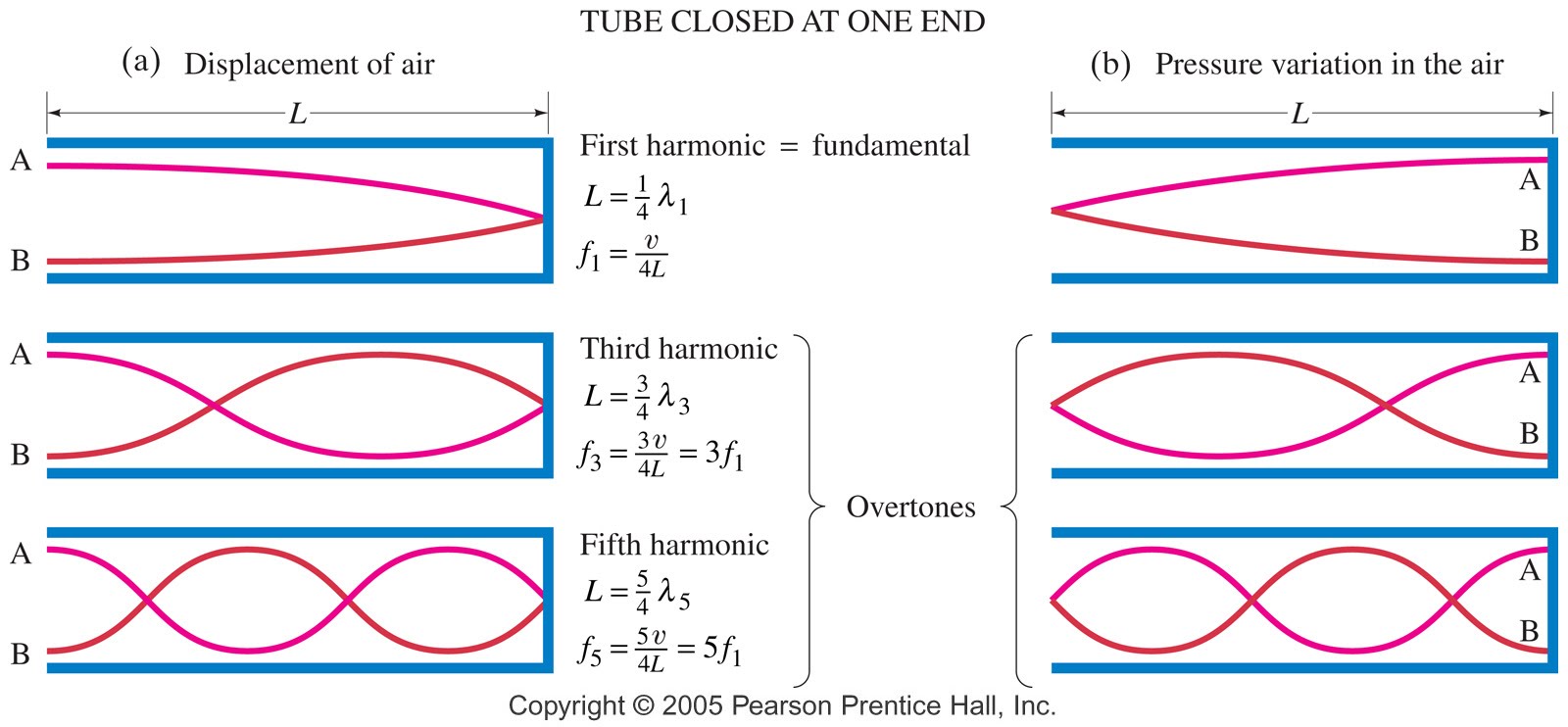

When you buzz into the mouthpiece, you create a standing wave (vibrating air column) inside the trombone, which produces a specific pitch. The trombone can be modeled as a tube with one end open (the bell) and the other end closed (the mouthpiece which you are playing into).

Image courtesy of Dan Russell, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

For now, the equation that’s useful here is

Where is the frequency, is the speed of sound, and is the length of the air column (the length of the slide).

Since pitch is frequency, and frequency is inversely proportional to the length of slide, extending the slide decreases the frequency, and thus lowers the pitch. Simple, right?

Uh, how about the notes beyond the seven positions?

Those notes need to be accessed with different “partials” achieved by changing your embouchure (lip and mouth technique).

Look at what the other diagrams are showing. When you play a note on a trombone (or any instrument actually), you’re not just playing the fundamental frequency (which is the main pitch you hear), but also a series of higher frequencies called overtones or harmonics. These overtones contribute to the unique timbre of the instrument and are why every instrument sounds different, even if they’re playing the exact same note.

Since the vibration of our lips is what creates the standing wave inside the trombone, changing the speed of our lips (e.g. by making it tighter) will “change the fundamental frequency” of the standing wave: if the frequency of our lips resonates (i.e. matches frequency) with one of the overtones, it amplifies it, making it sound like the “new fundamental frequency.” Yes: that means the higher we go, there will be “less” (or at least audible) overtones in the sound, making the tone sound more pure and closer to a pure sine wave.

By the way, when I say changing the speed of our lips is what selects the partial, while it’s technically true, it’s not a good way to teach technique.

Why not?

Just like how playing the piano isn’t just moving a finger up and down (even technically that’s all what’s happening) but instead involving the whole arm, to effectively control your trombone playing, you need to involve your tongue as well.

In fact, even if your lips are the main source of sound, your tongue actually does a lot of work in helping your lips with managing the air speed. Overstressing the lips is one of the most common mistakes beginners make when trying to reach the high partials. We call the overall technique of how you control your face to play into a wind instrument embouchure, and good embouchure is important for good sound.

Speaking of good sound, let’s talk about

Tuning!

Being a “continous pitch” instrument is both a blessing and a curse: while you technically have the capability to always be in tune, it also means there’s more responsibility on you with regards to tuning.

Whereas you can just press a key on a piano to make a sound, you have to physically adjust the pitch of the trombone to match the desired frequency. This includes adjusting the length of the slide, the tension of the lips, and even where your lips are positioned on the mouthpiece! Everything changes the sound slightly.

But, how can a trombone ever be better than the piano when there’s so many variables? Well, unlike a piano, where each key produces a fixed pitch, a trombone lets me subtly adjust every note as I play.

A little rabbit hole…

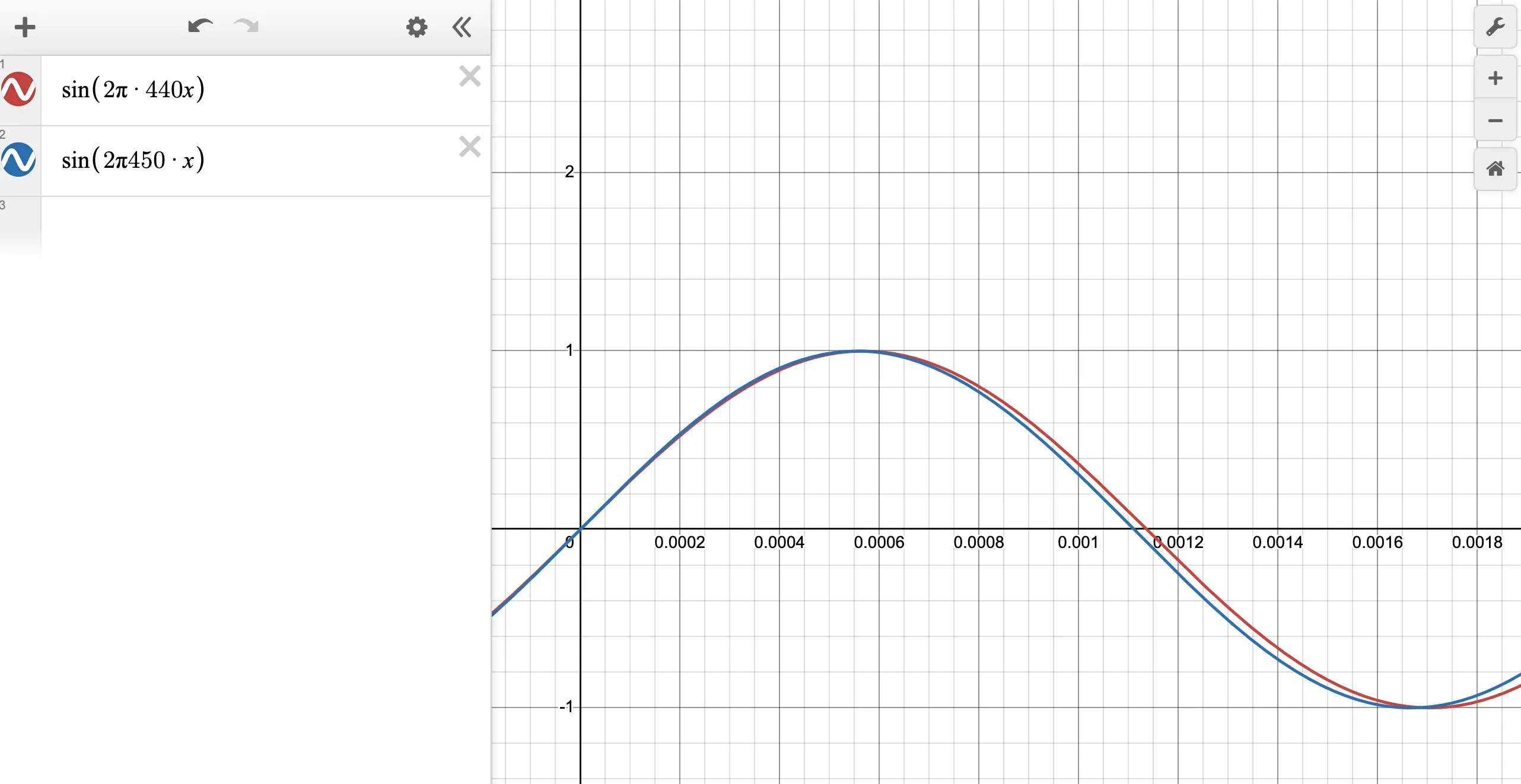

Here’s a little detour into musical instrument tuning systems. Let’s say I play a note at 440 Hz (this would be the standard A above middle C). Let’s say I were to play another note at 450 Hz. What would happen?

The two notes would sound slightly out of tune, creating a beat frequency of 10 Hz. This is because the frequencies are not exact multiples of each other. Since the human ear can detect small differences in pitch, these slight discrepancies can be perceived as dissonance or even unpleasantness. Nice-looking frequency ratios like 1:1 (octave), 3:2 (perfect fifth), 4:3 (perfect fourth), etc, sound “good” to our ears, because they’re the most resonant. This is called just intonation. In just intonation, we base the tuning of notes on each other using these nice ratios. Of course, that definition varies wildly depending on what note you are referencing and what intervals you use, and it could lead to really, really ugly intervals known as wolf intervals.

So, the modern piano isn’t tuned this way. That’s because we want be able to use the piano to play in all 12 keys. Everything should sound relatively good. Thus, the piano is tuned to a system that equally divides an octave into 12 equal parts, known as equal temperament. This system ensures that every key and every note sounds equally good, but it sacrifices the purity of just intonation.

But any instrument that’s not the piano or guitar can actually make micro-adjustments while playing a song. This means that we can actually have the nice-sounding just intonation without the hassle. For most wind instruments, this involves embouchure adjustments. For string instruments, this involves slight adjustments to the finger placement.

For trombonists, while you can also make embouchure micro adjustments, you can also just simply move the slide up or down.

In practice, I never actually think about “oh I have to tune this note around 13 cents flat than how I would normally play it because it functions as the third of this chord.” Instead, I am instead always listening to the rest of the band and I try to fit in my note before I play it. It’s not that deep: use your ears to determine if it sounds good or not.

Conclusion

While there’s a lot more aspects of the trombone (and brass instruments in general) I could talk about (such as the triggers or how to achieve good tone), this is the core of what I’ve learned about playing the trombone.

This blog post is hosted on GitHub. If you want a part 2 covering the other aspects, let me know!